Dorothy Cotton, June 9, 1930 - June 10, 2018

Dorothy Cotton's Life of Service Leaves Lasting Legacy

After a period of declining health, Dorothy died at her home on June 10, 2018. She was the highest ranking woman in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), directing the group's Citizenship Education Program (CEP) during the heyday of the Southern civil rights struggle. She earned a place in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s inner circle of executive staff and was part of the entourage traveling with Martin to Oslo, Norway, in December 1964 to witness his acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Dorothy was a consistent advocate of the notion that mass movements are not created by leaders but built from the bottom at the grassroots level. As she wrote in her 2012 memoir, If Your Back's Not Bent: The Role of the Citizenship Education Program in the Civil Rights Movement, Martin emerged out of a movement beyond the control of any one leader:

. . . his voice was heard explaining, challenging, teaching, justifying protest actions— but he did not start the actions. The people were energized; the people acted. He did not tell Rosa Parks to keep her seat; he did not tell the four students in Greensboro, North Carolina, to take seats at the Woolworth’s lunch counter where Black people were not allowed to sit (though we could shop at every other counter in the store). He did not tell Fannie Lou Hamer and Annie Devine to demand the right to vote in the Mississippi Delta. He did not tell the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth to take his bold action in Birmingham, Alabama, which was the catalyst for a hotbed of protest action and is still talked about around the world.

Born Dorothy Lee Foreman in 1930, Dorothy spent her childhood in Goldsboro, North Carolina, where she and her three sisters were raised, following the death of their mother in 1934, by their father, a tobacco factory worker. Upon graduating from high school, she left for Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, where she paid for her tuition by working as housekeeper for university president Robert Prentiss Daniel. When Daniel accepted a position as president of Virginia State College in Petersburg, Virginia, Dorothy transferred there to complete her undergraduate degree in English and library science. She and George J. Cotton were married shortly after graduation, and Dorothy soon went on to complete her master’s degree in speech therapy at Boston University.

Dorothy Cotton’s involvement with the civil rights movement began in the late 1950s, when she joined Gillfield Baptist Church in Petersburg and met its pastor, Wyatt Tee Walker. Encouraged by Walker, she became involved in local protests targeting segregation, and eventually became secretary of the Petersburg Improvement Association. When I interviewed her in 1990, she recalled that she first met King when the SCLC leader visited Petersburg. She immediately noticed “some intangible magnetic quality. . . that made people want to be with him … because he had a way of really being with you when he was with you."

In 1960 King invited Walker to come to Atlanta to serve as SCLC’s executive director, and Walker arranged for Cotton to become his administrative assistant. Cotton quickly pushed beyond the role of a traditional wife as she immersed herself in SCLC activities, becoming the group's educational consultant and then in 1963 education director of the CEP. Cotton described her responsibility as helping “people realize that they have within themselves the stuff it takes to bring about a new order.” She was active in teaching literacy, citizenship, and nonviolent protest tactics, and motivated others to become registered voters and active political participants. She spent much of her time with the CEP, traveling throughout the South and conducting educational programs with Andrew Young and Septima Clark.

As one of SCLC’s most influential leaders, Cotton established a close relationship with Martin Luther King. Not only a female leader among men but also one of the few SCLC leaders who had never pastored a church, she quickly gained the respect of her strong-willed colleagues. She came to admire King's ability manage the "different personalities and different talents" of her male colleagues, a group Martin once described as a "team of wild horses."

As the sole female SCLC administrator, Dorothy Cotton often spoke candidly about the difficulties she faced dealing with the strong egos of the male ministers who dominated the organization. But she eventually won their respect and admiration for her success in training local movement leaders, who were themselves often women. As her SCLC colleague Andrew Young recalled:

Dorothy assumed a very natural role as everybody’s sister. The men began to relate to one another through her. The precise enunciation and elocution of her speech demanded that her opinions earn respect. Her charm and effusive personality inspired admiration and also kept potential male admirers at bay; her quick wit crushed many egos.

Although many of her educational workshops was conducted at the CEP's Dorchester training center in southern Georgia, rather than near SCLC's Atlanta headquarters, Dorothy soon gained Martin's trust. During the 1963 Birmingham campaign, their relationship became closer when she joined other SCLC's staff members to mobilize youthful protesters who turned a probable defeat into SCLC's most crucial victory. By time of SCLC's campaigns in St. Augustine, Florida, and Selma, Alabama, Dorothy was widely recognized as one of SCLC's most effective organizers. Her unshakeable commitment to the ideals of nonviolent resistance to injustice matched King's. As she wrote in her memoir:

I actually could look at a policeman in Birmingham or St. Augustine, Florida, and feel compassion instead of hostility or fear, even as I was being beaten (or at least after our attackers stopped or we were able to leave). I eventually came to see the policemen as being damaged by the racist programming, structures, and institutions in and around which we all lived our lives. Just as important, I realized I was opening myself to seeing how this understanding of love was so deeply changing me that I related to people differently in every place where I interacted, including business, personal, and family relationships, with friends, and even with strangers in public places.

In a telegram applauding King's nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize, she told Martin of her admiration for “the seriousness and devotion with which you hold your noble charge.” Her relationship with King was not limited to SCLC work, as she pointed out that those working for the organization “were all friends as well as staff.” This friendship showed her a side of him that “was fun to be with. He was the life of the party”

Cotton retired from SCLC in 1972. Following her departure, she held jobs relating to public service and social action, including director of a federal Child Development/Head Start program in Birmingham, Alabama, and vice president for field operations at the King Center in Atlanta. In 1982 she accepted a position with Cornell University as their director of student activities. In the early 1990s, Cotton returned to her civil rights background and began leading seminars and workshops on leadership development and social change. She later became a founding member of the National Citizenship School, devoting to teaching the skills of creating publicly accountable institutions reflecting democratic ideals. Her many admirers later established the Dorothy Cotton Institute in Ithaca, New York, to promote the cause of human rights.

Dorothy's deep commitment and enormous energy led her to travel widely until the final year of her life. After I became director of the King Papers Project, our paths often crossed at conference and other events connected with King's legacy. I can't remember exactly when I first met her, but it was probably during one of my visits to the King Center during the 1980s. Whenever and wherever I encountered her, her energy and ability to capture the attention of audience was evident. Sometimes her talks would feature freedom songs, performed just as I imagine she would have sung during the turbulent 1960s. I especially remember when she spoke at the King Center's 1988 conference on Women in the Civil Rights Movement, a gathering that sparked scholarly interest in the role of women activists.

Dorothy first visited the King Papers Project (later the King Institute) in 1991. I remember discussing her plan to write her autobiography and encouraging her to use our resources. During the next quarter century, she would return often and generously made herself available to speak with my colleagues or students. I interviewed her on many occasions, and, as her writing progressed, invited her to stay on our home in Palo Alto. She was modest about the importance of her own historical role. I had to push her to tell her own story as well as the story of the movement. The resulting book was an major contribution to the expanding literature of the Southern freedom struggle.

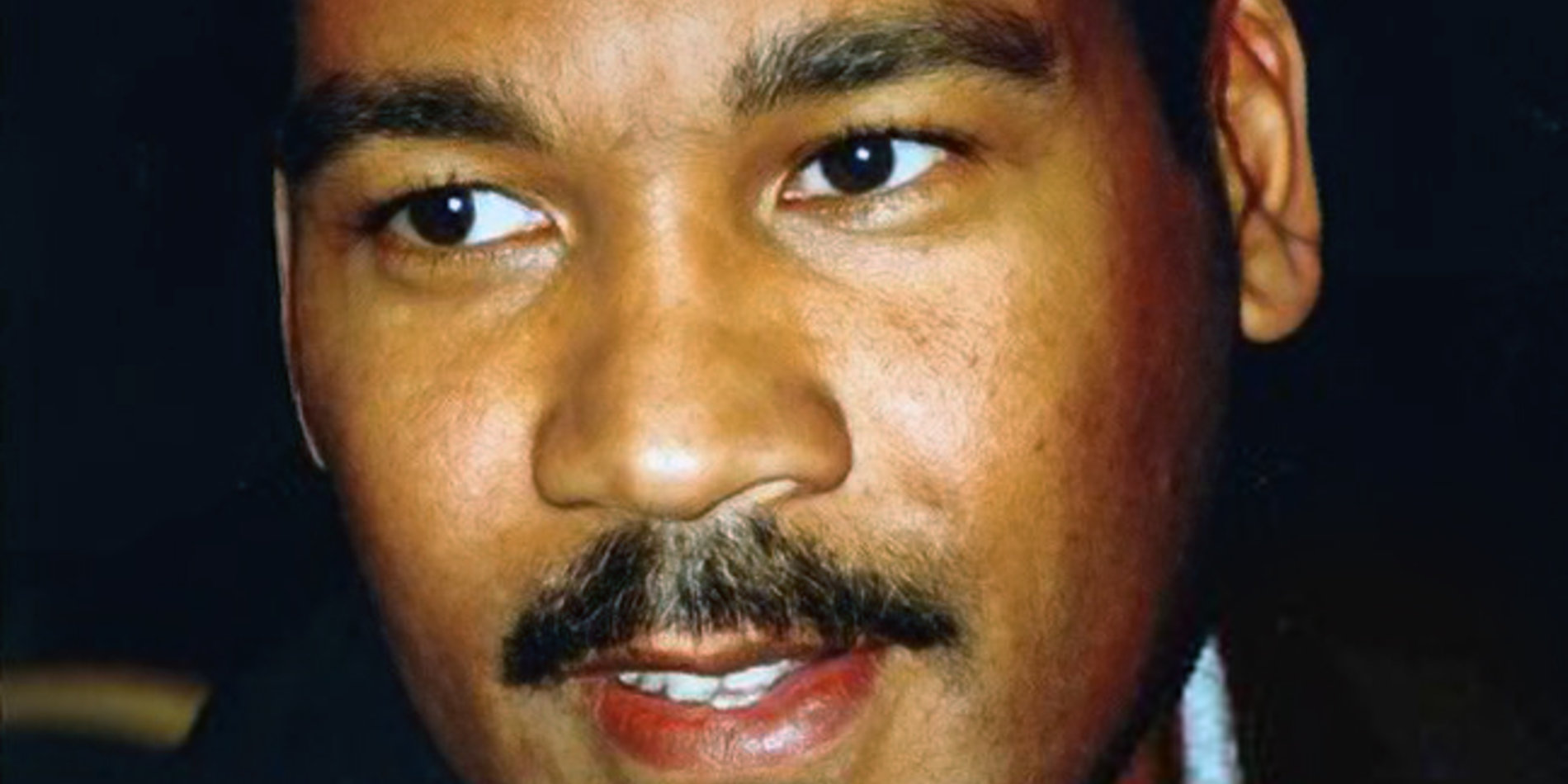

I always enjoyed opportunities to capture at least one facet of her personality in photographs, and these glimpses or her never failed to reveal something new about her. When we both attended the opening of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in 1992, I was able to learn more about her crucial role the crucial campaign that took place in Birmingham during the spring of 1963. A photograph I took of her as she talked at a private home in Birmingham reveals. her magnetic presence. Years later, I saw the fiery side of her persona when she spoke in 2008 in Memphis at a commemoration the 40th commemoration of King's assassination.

Dorothy's relationship with Susan and me became closer when she stayed at our home for several months while completing her memoir. Although, like many writers, she struggled to bring together the many strands of her life in a publishable manuscript, we enjoyed assisting her as she grounded her memories in the historical documents of the King Papers Project. The resulting book was a vital contribution to historical understanding of the role of grassroots leaders and of the extraordinary teacher who reminded ordinary people that they could and should play extraordinary roles in the struggle against racial oppression.

The King Institute's Scholar-in-Residence Clarence B. Jones praised Dorothy as “an indispensable cornerstone" of SCLC.

I was blessed to know, work with, and follow her leadership. During a time when men dominated the leadership of the Civil Rights Movement, Dorothy carried on the legacies of Ella Baker, Mary Church Terrell, Ida B. Wells Barnett, Rosa Parks Fannie Lou Hamer, and other heroines of our Movement. I loved and respected her so much. She will be painfully missed.